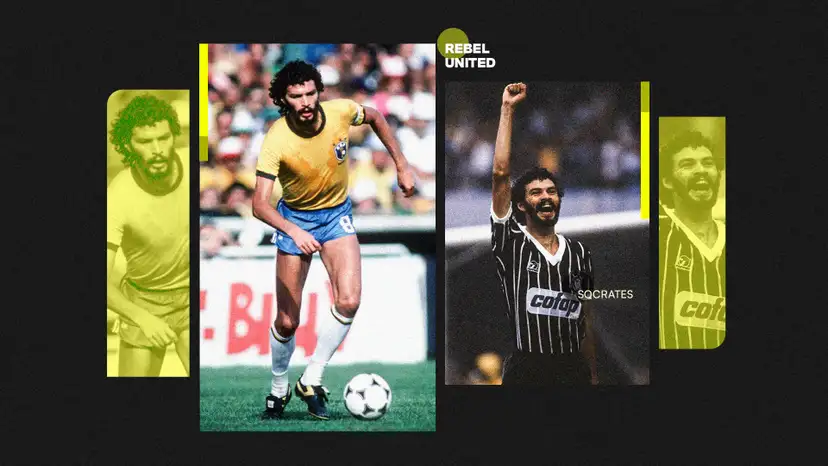

Rebel United: The Story of Socrates – Doctor, Activist, Genius

How the Brazilian Icon Redefined Football and Politics at Corinthians

In a world where footballers are often reduced to highlight reels and transfer fees, there once lived a man who was everything the game didn’t expect, and perhaps didn’t deserve — yet desperately needed. His name was Sócrates Brasileiro Sampaio de Souza Vieira de Oliveira, but the world simply knew him as Socrates.

The fact that he shared a name with the legendary Greek philosopher wasn’t just coincidence — it was destiny. The Socrates of ancient Athens was known for asking questions that shook the foundations of his society. The Socrates of Brazil did the same — not in a toga, but in a yellow jersey, blue shorts, and a white headband. He played football with elegance and purpose, yes, but he also used the game to challenge authority, ignite change, and leave behind a legend that went far beyond the pitch.

Socrates the Footballer: Elegance and Intelligence in Motion

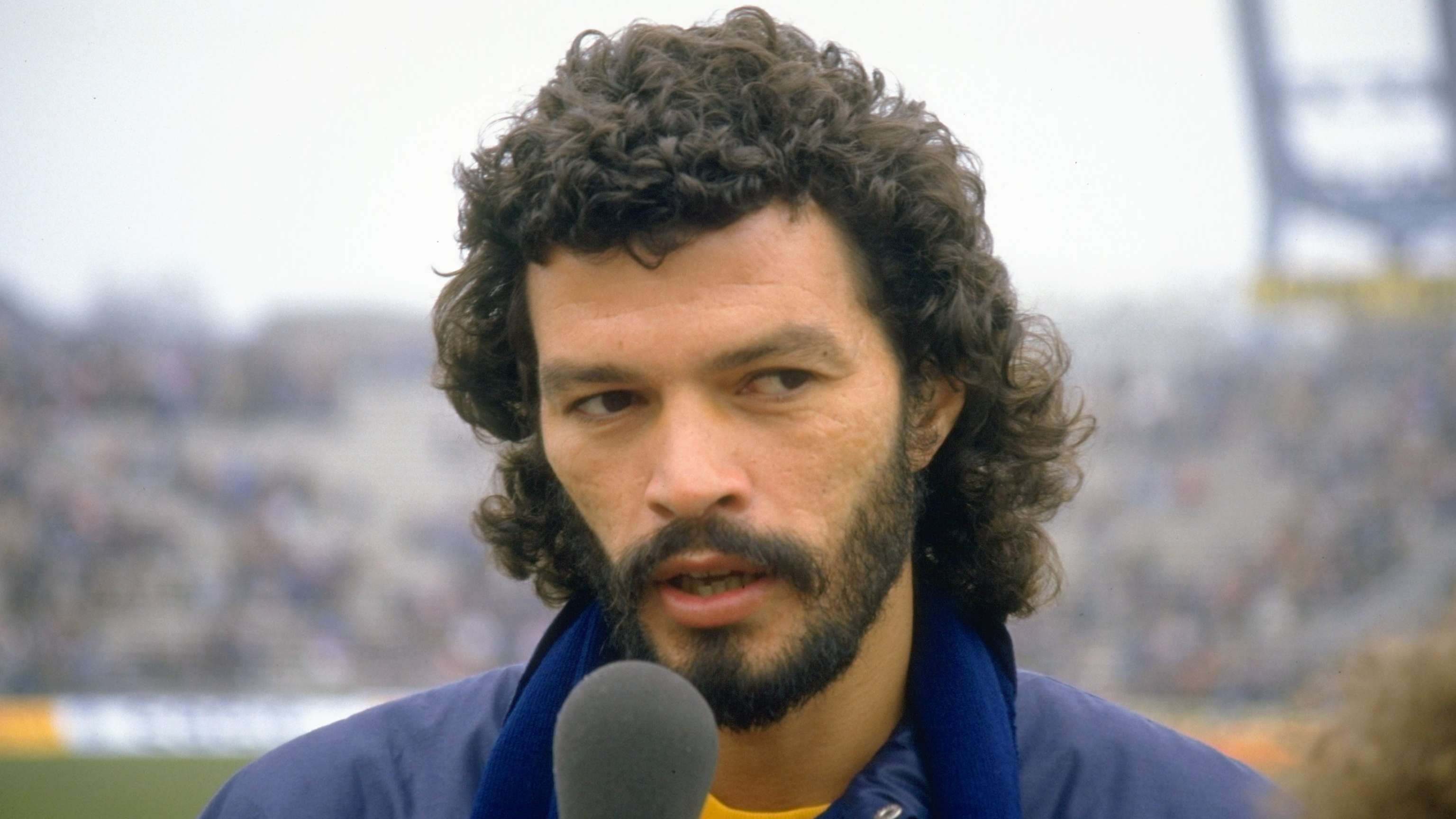

With his wiry 6’3″ frame, unhurried gait, and famously small feet, Socrates didn’t look like your typical football star. But once he had the ball at his feet, he was hypnotic — a player who saw the game in dimensions others didn’t. A creative midfielder with a penchant for backheel passes, Socrates pulled the strings for both Corinthians and the Brazilian national team throughout the 1980s.

He wasn’t a sprinter, nor was he obsessed with stats. But his intelligence — footballing and otherwise — allowed him to read the game with astonishing clarity. The great Pelé is said to have once remarked that Socrates “played better going backwards than most did forwards.” That about sums him up. His game was subtle but cutting, creative but clinical.

And then there was the flair. The headband, the raised fist, the shaggy beard — they weren’t just style. They were statements. On the biggest stage — the World Cup — he became an icon, appearing for Brazil in both 1982 and 1986. Though Brazil didn’t win either tournament, that 1982 team, with Zico, Falcão, and Socrates at its heart, remains one of the most beloved sides never to lift the trophy. Beautiful losers, maybe, but unforgettable ones.

The Birth of ‘Democracia Corinthiana’

Socrates Brazil 1982

For Socrates, football was never just about the sport. It was about society, and his club Corinthians became the perfect vehicle for his ideas.

In the early 1980s, Brazil was still living under a military dictatorship that had been in place since 1964. In this repressive climate, Corinthians took a radical step. With a new president, Waldemar Pires, and sociologist Adilson Monteiro Alves brought in as sporting director, the club gave unprecedented power to its players. Socrates, always politically minded, became the movement’s charismatic leader.

At Corinthians, decisions weren’t dictated from the top — they were voted on. Everything from matchday line-ups and training schedules to signings, sackings, and even the lunch menu was decided democratically. They even relaxed the infamous “Concentração” rule — which locked players in hotels the night before matches — trusting them instead to prepare like professionals.

The movement was called Democracia Corinthiana, and it was like nothing else football had seen. But it wasn’t just internal reform. Corinthians took their stand public. They wore shirts with slogans demanding political change: “Diretas Já” (Direct Elections Now) and “Eu quero votar para presidente” (I want to vote for the president). Socrates often donned headbands with messages like “No Violence” and “People Need Justice.”

In a time when speaking out was dangerous, they spoke loudly.

A Genius on and off the Pitch

Crucially, this democratic experiment didn’t come at the cost of success. Under Socrates’ influence, Corinthians won back-to-back São Paulo State Championships in 1982 and 1983 and came agonisingly close to winning the national title. Socrates himself was crowned South American Footballer of the Year in 1983 — a fitting accolade for a man who had become the soul of both a football team and a political movement.

His teammate and close friend, Walter Casagrande, later said: “There were many reasons for the success of our movement, but Socrates was one of the most important. We needed a genius like him — politically astute, admired by everyone. He was our shield.”

But like all revolutions, Democracia Corinthiana couldn’t last forever.

A Farewell and a Promise Broken

Socrates Brazil 1986

In 1984, during a political rally in São Paulo attended by an estimated two million people, Socrates delivered an ultimatum: if Congress passed a constitutional amendment allowing for direct presidential elections, he would stay in Brazil. If not, he’d leave for Europe.

The amendment failed. And so, true to his word, Socrates moved to Italy to join Fiorentina. It was a blow to the movement he had helped build. Though he returned to Brazil a year later — first with Flamengo, then Santos — something had changed. The magic of Corinthians’ democratic era was gone.

Final World Cup, Final Years

Socrates returned to the global stage at the 1986 World Cup in Mexico. But Brazil’s journey ended in the quarter-finals after a dramatic penalty shootout loss to France. Socrates missed his spot-kick. It was his last major international outing.

He retired from professional football in 1989 and returned to medicine — after all, he’d been a qualified doctor even during his playing days. He made a brief and symbolic comeback in 2004, aged 50, playing a single match for English non-league side Garforth Town. Ever the rebel, he did it just because he could.

Sadly, Socrates’ later years were plagued by health issues. A heavy drinker and smoker, his body eventually gave out. He died in 2011, aged just 57, leaving behind a footballing legacy unlike any other.

More Than a Player

To call Socrates simply a great footballer is to miss the point entirely. He was a thinker, a reformer, a voice of the people. He played football with the grace of a poet, but he also fought for justice with the heart of a revolutionary.

In the documentary Rebels on the Ball, presented fittingly by Eric Cantona — another footballer-philosopher — Socrates‘ story lives on. His impact is still felt, not just in Brazil but around the world, whenever football becomes more than just a game.

As Brazil’s former president Dilma Rousseff said upon his death: “On the pitch, he was a genius. Off the pitch, he was politically active, concerned about his people and his country.” And in truth, the two were never separate for him.

For Socrates, the game was never just about goals. It was about ideals. About making the beautiful game serve a beautiful purpose.

There are no comments yet. Be the first to comment!