“You’re Not Just a Tennis Player”: The Human Side of Tennis in a Ruthless Era

How Amanda Anisimova and others are reshaping the narrative around mental health in tennis

On the surface, tennis is a beautiful game: graceful footwork, thunderous winners, the roar of a crowd as a match flips on a dime. But beneath the bright lights and Grand Slam glories, there is another story quietly unfolding—one of burnout, anxiety, emotional fatigue, and players learning the importance of stepping back.

At this year’s Wimbledon, Amanda Anisimova stands just one match away from her first Grand Slam final. It’s a position many tipped her to reach years ago. But what makes this moment so powerful is not the potential for silverware—it’s how far she’s come off the court.

Amanda Anisimova: A Comeback Built on Self-Care

In 2019, Anisimova was a teenage sensation. Just 17, she stunned the tennis world by reaching the French Open semi-finals, toppling defending champion Simona Halep along the way. The world ranking climbed, expectations soared, and the pressure quietly tightened around her.

Fast forward four years, and the racquet was down. Anisimova, drained mentally and emotionally, took a break from tennis. Not a week. Not a month. She left completely. She stopped training, enrolled in university classes, travelled, spent time with friends and family—and, crucially, stayed away from tennis.

“I found it unbearable to be at tournaments,” she admitted in an interview with BBC Radio 5 Live. “I learned a lot about myself, my interests off the court, and just taking time to breathe and live a normal life.”

Anisimova’s words echo louder in a sport known for its relentless calendar. With tournaments running 11 months a year, players rarely get more than a few days’ break between time zones and tour stops. Prize money and ranking points are ever-dangling carrots. The pressure to perform becomes suffocating. The court—once a sanctuary—can suddenly feel like a cage.

More Than a Match: Mental Health in the Spotlight

Anisimova is not alone. Tennis is slowly, finally, shedding its silence on mental health.

Italian star Matteo Berrettini described a “heavy” feeling when returning to the court after injury layoffs. Alexander Zverev, the world No. 3, admitted recently: “I was lacking joy. Inside and outside tennis. I’ve never felt this empty before.”

Andrey Rublev, a regular presence in the ATP top 10, worked with a psychologist to cope with overwhelming anxiety and a growing sense of directionlessness. “Tennis is just the trigger point,” he told The Guardian. “It’s something inside you that you need to face.”

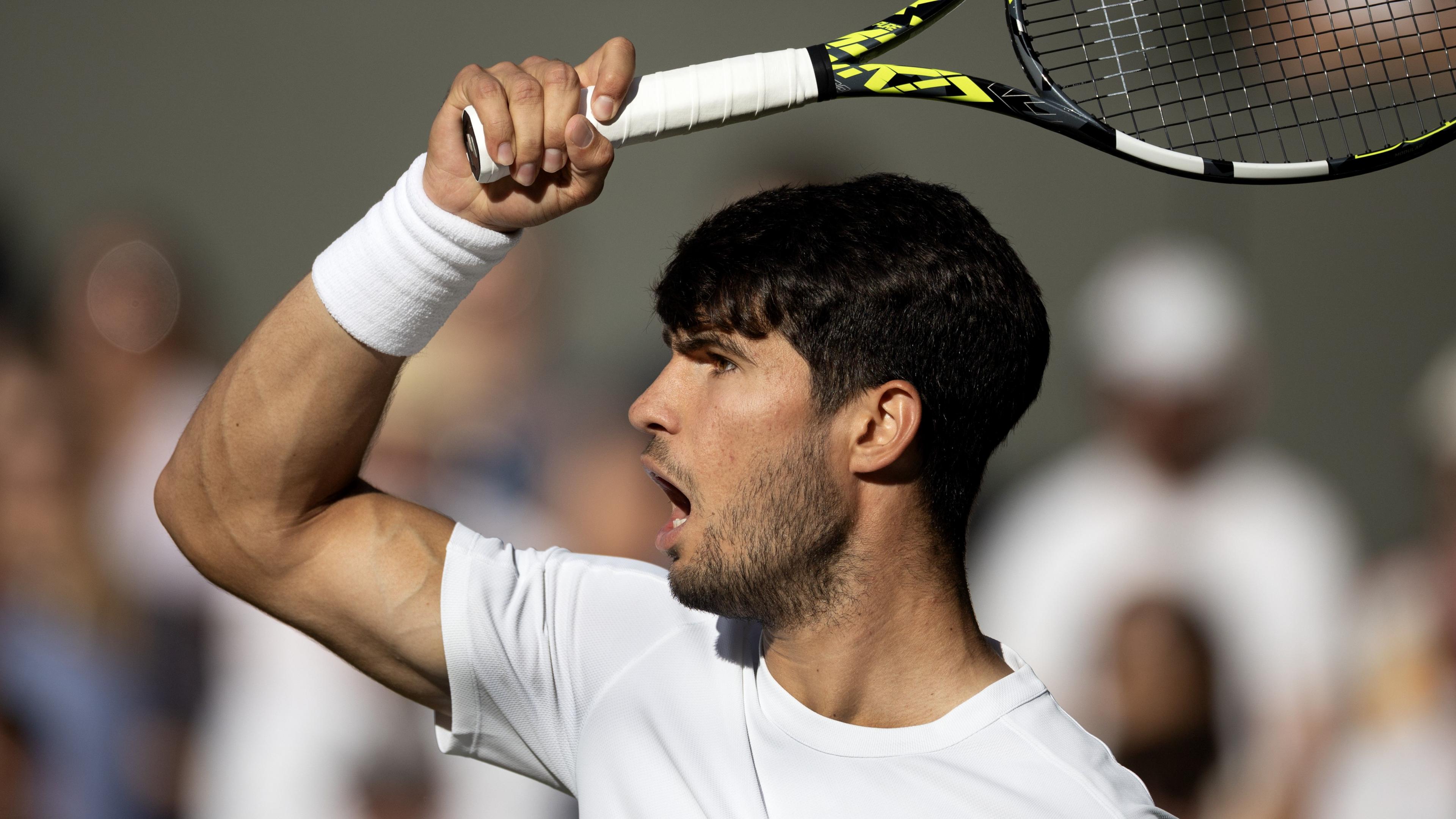

Even Carlos Alcaraz, still just 21 and already a five-time major winner, confessed in a Netflix documentary that his biggest fear is tennis becoming an obligation rather than a joy. That honesty, from such a young and successful star, speaks volumes.

“You’re Not Just a Tennis Player”

Amanda Anisimova throws the ball to serve in her Wimbledon quarter-final against Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova tennis

It’s a phrase many now cling to in the tennis world. Madison Keys, an Australian Open finalist and WTA veteran, captured it perfectly:

“From a pretty young age, our identity becomes very wrapped up in being a tennis player,” she said. “That’s great, but when you have tough weeks, months, or years, that can take a toll on how you think about yourself.”

Keys turned to therapy—not just sports psychologists but therapists who focused on her as a whole person. “Being able to dive into that and separate the two—that you’re not just a tennis player, but a full person with other interests and qualities—that changed everything.”

Aryna Sabalenka, world No. 1 and known for her power game and emotional intensity, worked with a therapist for five years. She recently shared that she now serves as “her own psychologist,” having learned how to talk openly with her team.

“They’re not going to judge me. They’re not going to blame me. They’re going to accept it, and we work through it,” she said.

The Cost of Chasing Greatness

The problem is systemic. Tennis players grow up defining themselves by their ranking, their last result, and how well they “handled the pressure.” The pursuit of glory demands sacrifice. But when the sacrifice becomes your sense of self, the cost is too high.

“You tell Sascha [Zverev] to take a break, it will get tough for him,” Rublev said. “He would love to play. But it’s not easy to step away.”

Carlos Alcaraz, despite his rapid rise, has found balance through joyful tennis and off-court escapes—like trips to Ibiza, which his team frowns upon but he insists keep him grounded.

“It’s about having fun, enjoying the game, and not thinking about the result,” Alcaraz said. “Just live in the moment.”

Finding the Way Back

Carlos Alcaraz hits a forehand during his Wimbledon quarter-final win against Cameron Norrie

Amanda Anisimova’s return to form didn’t come overnight. After her hiatus, she had to rebuild—physically, mentally, emotionally. She put in the hours, returned to the grind, and re-learned how to compete. In February, she won the biggest title of her career at the WTA 1000 in Doha. Now she’s back in the world’s top 10 and back on Centre Court.

But more importantly, she found herself again.

“It was something I needed to do for myself,” she said. “It’s been a journey. I finally found my game and my confidence.”

Tennis Is What They Do, Not Who They Are

There’s a growing acceptance across the sport that mental health isn’t a weakness to be hidden, but a reality to be managed. Players are reminding themselves—and each other—that they’re not machines. They’re not defined by rankings or trophies. They’re people first.

Tennis may be their career, their craft, their passion. But as the new generation reminds us: it’s not all they are. And maybe, just maybe, that truth is what will help them play their best tennis yet.

There are no comments yet. Be the first to comment!